Tàijíquán

Taijiquan is an internal martial art which is of debatable origins, but was conclusively systematized by the Chen family in Henan during the Ming Dynasty.

Zhang Sanfeng

The legendary creator of taijiquan was martial artist and Daoist ascetic, Zhang San Feng. Zhang was born in the secluded southern province of Fujian during the decline of the Song Dynasty and famously lived well into the Ming Dynasty as late as the 15th century. He is revered as a legend in many Daoist temples for having achieved enlightenment/immortality but is especially considered as the patriarch of Wudang internal martial arts. Zhang was a scholar and philosopher; in his early years he held political office as a magistrate and later in life he took to asceticism and became a wandering hermit, famously disappearing into the mountains for many years on end. In total Zhang lived more than 200 years and became the fascination of several emperors who would send out envoys in an effort to find Zhang and compel him to come to court and teach. One emperor went as far as to build an enormous palace and dedicated it to Zhang in hopes that it would lure him out of seclusion but he was unsuccessful.

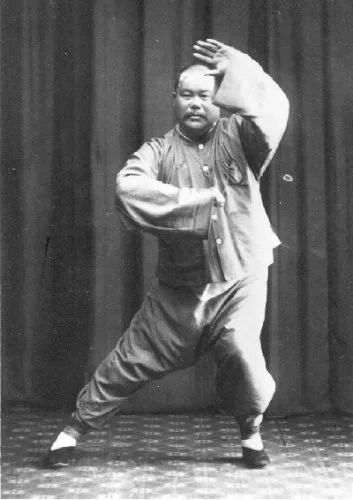

Chen Changxing

Inspired by Daoist philosophy and his own studies and cultivation, Zhang developed practices which brought the body into a state of harmony with nature and self. He shared his practice with other Daoist monks as well as some laymen. Zhang is said to have taken a student called Wang Zongyue who went on to develop the theory and practice of taijiquan, authoring the Treatise on Taijiquan, which outlined many of the essential tenets of the practice. Furthermore, Wang was the teacher of Chen Wangting, the founder of Chen family style taijiquan.

A contemporary of William Shakespeare, Galileo, and Rembrandt, the 17th century military commander Chen Wangting - 陳王庭 formalized the practice of taijiquan into what was called at the time long boxing or soft boxing. Chen was the first to formalize this practice into a family art and had a major influence on the growth and development of the practice. The Chen family exclusively held this art for six generations until the first student was accepted from outside the family. In the 1820s Yang Luchan came to study with Chen family patriarch Chen Changxing. He took seriously the study of Chen soft boxing and once he was sufficiently adept he departed for Beijing where he would take on students of his own. From Yang Luchan emerged what would become the most well known and widespread style of taijiquan.

Sun Lutang

Yang Lu-chan (1799–1872) was a renowned Chinese martial artist and the founder of Yang Style Taijiquan, one of the major styles of Tai Chi Chuan. Born in Yongnian County, Hebei Province, China, Yang Lu-chan initially worked as a servant in the Chen family in Chen Village. During his time there, he learned Chen Style Taijiquan, a martial art that was traditionally kept within the Chen family.

Yang Lu-chan's martial skills earned him the nickname "Yang the Invincible." Legend has it that he was able to defeat other martial artists without much effort. However, because he was an outsider, he initially faced challenges in learning the complete Chen Style form.

According to historical accounts, Yang Lu-chan observed the practice secretly and was eventually discovered by Chen Chang-xing, the head of the Chen family. Recognizing Yang's skill and dedication, Chen Chang-xing accepted him as a disciple and taught him the full Chen Style Taijiquan.

After years of training, Yang Lu-chan modified the Chen Style, creating a new style that was softer, slower, and more accessible. He emphasized principles such as relaxation, balance, and controlled breathing. This modified style became known as Yang Style Taijiquan.

Yang Lu-chan began teaching his new style in the Beijing area, and his reputation as a skilled martial artist and teacher grew rapidly. His fame reached the imperial court, and he was eventually invited to teach Taijiquan to the imperial family, including the emperor's bodyguards. Yang's contributions to martial arts, particularly the creation of Yang Style Taijiquan, laid the foundation for the development and popularization of Tai Chi as a holistic practice.

Yang Lu-chan's teachings were passed down to his sons, Yang Ban-hou and Yang Jian-hou, who further refined and disseminated the Yang Style. The style continued to evolve through subsequent generations, with Yang Cheng-fu, Yang Lu-chan's grandson, playing a key role in promoting Yang Style Taijiquan as a health-promoting exercise accessible to people of all ages.

Yang Jianhou (1839–1917) was a prominent Chinese martial artist, serving as the eldest son of Yang Lu-chan, the founder of Yang Style Taijiquan. In the early stages of his training, Yang Jianhou, along with his younger brother Yang Ban-hou, learned martial arts directly from their father, drawing on the Chen Style Taijiquan teachings acquired through their family's connection with the Chen family in Chen Village. Renowned for his martial expertise, Yang Jianhou's movements were characterized by a blend of power, agility, and precision, contributing significantly to the refinement of the Yang Style. His role extended beyond personal practice, as he passed on his martial knowledge to his sons, including Yang Shaohou and Yang Cheng-fu, who played pivotal roles in the continuation and diversification of the Yang Style Taijiquan. While Yang Jianhou may not have achieved the historical prominence of some other family members, his emphasis on martial applications and traditional aspects of Tai Chi has left an enduring legacy, contributing to the richness and diversity of the Yang Style. His influence is appreciated by those who value the martial aspects of Tai Chi, and his contributions continue to shape the practice and study of Yang Style Taijiquan today. Yang Jianhou passed away in 1917, leaving a lasting impact on the development of Yang Style Taijiquan and the legacy of one of the most widely practiced forms of Tai Chi worldwide.

Yang Ban-hou's (1837–1892) approach was more forceful and martial in nature. He emphasized the martial applications of Taijiquan and was known for his strict teaching methods, demanding precision and dedication from his students.

Despite his formidable martial skills, Yang Ban-hou faced personal challenges, including health issues. He suffered from tuberculosis, which ultimately led to his early death at the age of 55. Despite the brevity of his life, Yang Ban-hou left a lasting impact on the evolution of Yang Style Taijiquan.

Today, Yang Ban-hou is remembered as a skilled martial artist and an important figure in the transmission of Yang Style Taijiquan. His influence is evident in the diversity of approaches within the Yang Style, with practitioners choosing to emphasize different aspects of the art based on their preferences and goals.

Yang Chengfu

Yang Chengfu was a prolific teach and accomplished martial artist in his own right. He encouraged his students to write books, take the practice out into the world, and to spread taijiquan. One of his students, Zheng Manqing came to be the liaison who spread taijiquan to America. Zheng would move to Manhattan in 1964 and teach taijiquan to an eager culture of Americans interested in the east.

Taijiquan enjoyed a cultural bloom in the 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s as many westerners came to take up eastern spiritual practices. The practice also grew extensively in southeast Asia during this time primarily as a result of the prolific teaching and accomplishment of Huang Xingxian (Huang Sheng Shyan), a highly skilled student of Zheng Manqing who would go on to do demonstrations of his taiji skill throughout the indo-pacific and set up 40 schools. The most notable demonstration from Huang came in 1970 when, at the age of 60, he agreed to a long-standing challenge from Mongolian shui jiao wrestler Liao Kuangcheng. Despite being significantly lighter and older than Liang, Huang went on to win the match 26-0. This headline launched the taijiquan master to new levels of fame.

The treatise on taijiquan

Taiji comes from Wuji

and is the mother of yin and yang.

In motion Taiji separates;

in stillness yin and yang integrate and return to Wuji.

It is not excessive or deficient;

it follows a bending, adheres to an extension.

When the opponent is hard and I am soft,

it is called departing.

When I follow the opponent and he is overwhelmed,

it is called adhering...

...Let the qi sink to the dan tian.

Don't lean in any direction;

suddenly appear,

suddenly disappear.

If pressed on the left, empty the left.

If pressed on the right, empty the right.

If the opponent rises, I seem taller;

if he sinks, then I seem lower;

advancing, he finds the distance too far;

retreating, I am upon him at once.

A feather cannot rest

and a fly cannot alight

on any part of the body.

The opponent does not know me;

I alone know him.

This is the mark of the superior boxer.

There are many boxing arts.

Although they use different forms,

they generally don't go beyond

the strong dominating the weak

and the slow resigning to the swift.

The strong defeating the weak

and the slow hands ceding to the swift hands

are all the results of natural abilities

and not of well-trained techniques.

There is a principle which demonstrates this.

A force of four ounces deflects a thousand pounds....

-Wang Zongyue

Theory

The practice of taijiquan / 太极拳 is fundamentally rooted in understanding body mechanics and in cultivating a somatic awareness of the separation and integration of yin and yang within the body. This practice alone is sometimes referred to as liang yi quan / 兩儀拳 today.

Body mechanics involves a study of weight distribution and of alignment with relationship to one's own body and to that of an opponent. For every movement there is an ideal vector and weight distribution to maximize effect. Two equal opposing forces, for instance, when situated in direct opposition, neutralize one another. If one is stronger it overcomes the other, but this involves the use of pure force. If one meets the other at an oblique angle, however, the force required to overcome diminishes exponentially. This is the basic principle introduced by the concept that a force of four ounces can deflect an opposing force of a thousand pounds. This is accomplished by glancing and this is one principle among many with respect to body mechanics.

Within nature there is a dynamic balance of yin and yang forces. Yang manifests in mountains and in the heavens. Yin manifests in lakes and in the earth. Man exists between heaven and earth, an expression of the yin and an embodiment of the yang. Within the body there is a natural reversal of the polar forces in the environment. Yang qi enters the head and the hands, and it becomes yin, sinking. Yin qi enters the feet and perineum, and becomes yang, rising. This a natural phenomenon which follows from the principle that opposites attract. So a net yang quality in the sky attracts the yin within a body to the top of the head and a net yin charge in the ground attracts the yang to the feet and to the pelvic basin. This is dynamic polarization. The separation of yin and yang creates potential energy. The recombination of these two forces is kinetic energy. By practice, it is possible to further polarize the body. Within taijiquan, this is accomplished by banking yin energy from the earth by exercising the yin channels in the legs (spleen, kidney, and liver) which are the conduits for drawing yin qi from the earth into the abdomen.

The rising movement of yin earth energy toward the head is a function of the wood element and the descension of yang heaven energy toward the pelvis is a function of the metal element. These two movements comprise the dynamic axis of the yin-yang interaction. The yin energy itself is represented by the water element and the yang energy is represented by the fire element. These four component make up the first evolution of of yin and yang, and describe the four directions - rising in the east, high in the south, sinking in the west, low in the north. The earth element sits in the center of this activity and represents stability.

The next evolution of yin and yang energy is that of the bagua or eight trigrams, which describes the four cardinal directions and four more intermediate phases. This is the basis for the more complex 64 transformations of the Yi Jing (The Book of Changes) which is a system of divination, philosophy, and mathematics fundamental to Daoism, Chinese culture, and Chinese medicine. It is from these eight trigrams that the basic movements of taijiquan are derived.

The Eight gates

履 - ☷ - Yield - Earth

列 - ☳ - Split - Thunder

擠 - ☵ - Press - Water

肘 - ☱ - Uproot - Lake

靠 - ☶ - Ram - Mountain

按 - ☲ - Subdue - Fire

採 - ☴ - Pluck - Wind

掤 - ☰ - Repel - Heaven

The practice of taijiquan involves a series of movements practiced with great care and intention, each of which represents one of the eight phases of the bagua. This practice teaches us not only how to fight, but how to navigate life. Because the Yi Jing transformations describe situations encountered in nature and in human life, understanding the principle dynamics of the bagua through physical embodiment imparts somatic understanding and subconscious wisdom about how to harmonize with the situations at play around you. Mastery of taijiquan is a lifelong endeavor.

I had a teacher who gave this simple advice: No matter what is wrong in your life, whether you are out of money or broken hearted, whether you are sick or you are angry or whatever problems you have in your life, just put your focus on practicing the taiji form. Practice with sincerity of heart three times per day and your life will improve. For the twenty or thirty minutes while you move through the form, think only of what is right in front of you, of the posture you are holding, and I promise, in one month your life will be better. All you have to do is practice.